10 October 2023, 12.15: From Hydro to Nuclear Power. The Role of Water in the Soviet Nuclear Industry

Researcher, Author, Energy Historian

As my last credited course during my PhD-education, I participated in the Occupy Climate Change Online School during this spring term. The online school, being organised by a team of renowned international scholars headed by Marco Armiero and administered by Anja Moum Rieser, brought together many different lectures about political ecology, environmental justice, and political science with a focus on the climate crisis, decolonialism, and just energy transitions.

I am glad that I was able to participate and to learn so much. My thanks and regards go to the many teachers in this course, who, and that is the most important thing in my view, taught us things that were dear to their hearts, with a conviction that change is indeed possible. The course was characterised by its international participants from many corners of the world. Being part of something that combines so many different worldviews and opinions on the basis of one joint struggle was very inspirational to me.

Of course, we also had to fulfil a final course assignment. Mine was about the climate crime that took place in January this year in Lützerath, Western Germany. As it is usus in this course, the finished products are published in the Atlas of the Other Worlds. In the following I will give a brief introduction to my piece. If it catches your interest, you can find the full version here, in the atlas.

Abstract

On 14 January 2023, the international climate movement met at the lignite open pit coal mine Garzweiler in Western Germany to protest the continuous mining business of the corporation Rheinisch-Westfälisches Elektrizitätswerk, better known as RWE. The culmination point of years of protests was the little village of Lützerath, which was squatted for about two years to prevent RWE’s large digging machine to destroy its houses and to get to the coal beneath it. On this day, 30,000 – 39,000 people travelled to the pit colloquially known as “Mordor”, an huge desert-like moonscape, with coal power plants blowing their climate-destroying fumes into the air, clearly visible at the horizon. It was a powerful protest, but it was futile in the end. Lützerath was destroyed and the coal is being dug up, public climate commitments, the Paris climate agreement, and protests notwithstanding. To add injury to insult, the German green party both ruled the federal energy ministry and the regional environmental ministry concerned with Lützerath: Instead of fighting RWE, they embraced the company’s goals and sanctioned the destruction of the village.

Together with others I travelled to Lützerath and took part in the protests. In the following I have interviewed five fellow protestors in a semi-structured manner. Following their testimonies, a small article has been written that documents what happened there and how the climate injustice took place in Germany.

If you want to read the full text, you find it here.

At this point I would also like to point to the Environmental Humanities Lab, which recently became a centre, at my division of history of science, technology and environment at KTH Royal Institute of Technology. Marco Armiero used to be its director and created together with others this excellent research hub. The online school was organised under its umbrella. If you want to, check out their website and their wonderful programme for the upcoming autumn term. At the moment, Adam Wickberg acts as interim director, until Robert Gioielli takes over as new associate professor for environmental humanities at out division from 01 January 2024.

Right now I am sitting in a study room at a hotel in Bern. The Suisse capital is beautiful. At the moment we are living through a heat wave that at least for me is the hottest I have felt this summer. I guess that is no surprise, given the fact that I am regularly based in Stockholm. I am participating in this year’s ESEH-Conference here. The European Society for Environmental Humanities had invited panel proposals on environmental topics. Aske Hennelund Nielsen from Erlangen and me worked together and created the panel “Nuclear Environments. Waste, Animals, Water and Infrastructure in the 20th and 21st centuries.”

The panel, chaired by Melina Antonia Buns (Stavanger University), features apart from Aske’s and my presentation excellent contributions from our colleagues in Linköping. Axel Sievers will speak about “Nuclear Space and Storage Natures. Fixation of Ecologies, Naturalization of Waste and Uneven Development”. Anna Storm and Rebecca Öhnfeldt will talk about “Caring for wild animals at nuclear power plants. A local emotion management device?”.

If you are also in Bern and joining the conference, please consider joining us at Unitobler (Yes, Toblerone!) F 022 on Friday morning 9-10.30am.

Abstract:

Nuclear technologies have played a decisive role in shaping natural environments since 1945. Atomic weapons have shaped landscapes and geographies through sustained nuclear testing, creating topographies of craters and distributed radioactive isotopes throughout the atmosphere on a global level. Nuclear power plants have through their construction upset waterways and shorelines and created new environments to better suit the placement of atomic energy installations. Animals have found themselves trapped within these changing environments, at the mercy of the Nuclear Industry and the personal of nuclear sites. Nuclear technologies have not only created physical craters and contaminated landscapes, but also mental craters, forcing scientific and local actors to mediate these changed environments. The mounting challenges of nuclear waste storage and re-naturalisation of formerly nuclearized landscapes pose theoretical and epistemological questions.

With this panel, we wish to examine some of the many ways that nuclear technologies have impacted, shaped and transformed environments as well as the scientific discourses on these altering settings. The panellists discuss how different nuclear technologies and their usage has (re)formed environments since 1945, using different both national and international cases. In particular we examine France, the western Soviet Union, Sweden, the UK, and the US in an international perspective.

The panel consists of both junior and senior scholars from different research institutions in Germany and Sweden working with new perspectives and approaches on how to make sense of the nuclear environment of the past and today.

Hopefully you have all had a great summer, including some well-deserved vacation, icecream, sunshine, and – depending where you are – some refreshing swims! As my doctoral education is slowly but surely coming to a close, it is time to give a brief overview where I am and what the stepping stones are, I still need to reach.

As of now, there is only about half a year left to finish my dissertation. All parts of my cumulative dissertation based on articles are fairly developed. In my kappa, the text that frames the thesis and discusses theory, research questions, and the actual technocratic culture analysis, I am focussing right now on updating the literature review. Here I am thankful for the valuable comments that I got from Eglė Rindzevičiūtė during my final seminar at the Division of History of Science, Technology and Environment at KTH. It is important to relate my work, especially my theoretical contribution regarding technocratic culture, to that of established scholars in the field. Apart from the literature review, I need to adjust the conclusion accordingly. Then I only need to shorten and improve the text.

My first article discussing South-Ukraine Energy Complex is already accepted in the journal Europe-Asia Studies and is scheduled to be published in 2024. Apart from the proofs, I am not expecting to do anymore work on this one.

The second text is the book Per Högselius and me have been writing together about the Soviet nuclear archipelago. Here the main work has been done and the finalised manuscript is with the publisher, Central European University Press. There will be one last round of edits, which cannot be substantial.

Number three about the creation of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the genesis of a technocratic working culture on-site had been handed in to NTM Technikgeschichte at the beginning of this week. I expect quite a lot of work that still needs to flow into this one before it can be published. But regarding the dissertation, it has developed far enough.

Article number four is also about Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. But it focusses purely on an interpretation of this nuclear power plant from an hydropower planning perspective. Chernobyl will be interpreted as the 7th extension to the Dnieper Cascade, a series of six subsequent hydropower plants along the Dnieper. In another future article I will discuss the knowledge transfer that took place here. But for this dissertation, article number four will focus on the links between the Dnieper Cascade and Chernobyl. A draft exists, but it needs substantial work to go into it. If you are interested about that one, you can listen to my presentation at the upcoming ESEH Conference in Bern in the Panel “Nuclear Environments” that Aske Hennelund Nielsen and me have organised and that takes place on Friday morning next week.

Text number five is a chapter in the edited Nuclear Water Nexus Volume about the fishing enterprise in the contaminated cooling pond of Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. This text as well as the volume is with the publisher now. I assume there will be major edits needed to it. Once again, for the context of the dissertation it should be in decent form though.

The last article of my dissertation is written together with Kati Lindström about the Estonian Nuclear Power Plant never actually built at Võrtsjärv. This text is in the writing stage and our developed draft needs to be finished.

Apart from the finalisation of all of these texts, my manuscript needs to pass the evaluation of an external reviewer first. I will hand it in most probably in September and hope for it to be accepted soon. Next, a lot of formalia need to be in place and the committee as well as my opponent need to agree upon a date. But this is taken care of by my main supervisor, Per Högselius. Last but not least the dissertation needs to be printed and distributed. All in all I hope to defend my dissertation in February 2024. But in the past I that date has been postponed because of reasons outside of my influence, so we need to be realistic about this.

In general I will focus on my writing during the höst termin. Apart from that I will continue to act as the PhD-representative for history and philosophy at our department. Occasionally I might step in as a teacher in our Swedish Society course. Next week I will be presenting in Bern at this year’s ESEH Conference. In September there will be a workshop on energy transitions at Södertörn University in Stockholm which I helped to organise and I was invited to the KTH WaterCentre to give a talk about my research. Besides these tasks, I will try to stay away from any more time-consuming commitments. Let’s hope that everything works out! Any major updates will be posted here.

The following essay is a repost from a text written by me and published on the blog Undisciplined Environments on 31 March 2021. Check out the blog! It is wonderful and lots of interesting people publish there on relevant topics regarding climate change, social change, and energy transition.

In a global state of climate emergency, technocratic voices for nuclear renaissance to curb greenhouse gas emissions are becoming prominent. The current anniversaries of the disasters at Fukushima (10 years) and Chernobyl (35 years) demand a reflection.

Nuclear energy as a contributor for the mitigation of global warming is heavily discussed among environmentalists and nuclear experts. While it is clear that fossils need to be replaced by alternative energy sources, people divide around the question whether nuclear could be an option for the future.

A debate surfaced after the ecomodernist manifesto proposed a technocratic approach in 2015, supporting the benefits of technofixes in a world which would be split into culture and nature. Political ecologist Giorgos Kallis disagreed, arguing with Latour and Žižek for the inseparability of human society and nature. He also argued against large technological systems, since such systems would result in the division of society into consumers and experts – and who could then challenge the experts? For him, this could not be ideal, since “a society powered by nuclear energy [could not] be a society of equals or of mutual aid.”

In the meantime, Robbins and Moore did not see this strong divide and rather saw themselves mediating for common ground between ecomodernists and environmentalists. Five years later, their theories were put to the test, as nuclear historian Kate Brown has found herself in a very practical struggle, after publishing Manual for Survival.

She analysed Chernobyl’s negative health consequences in Belarus and Ukraine on the basis of declassified material in central and county archives, supplemented by oral history. Quickly she got attacked by nuclear experts, challenging her interpretation of source material with an alleged lack of knowledge about radioactivity. By turning towards flora and fauna, she was able to add so-to-speak living archives of radioactive contamination.

It was a struggle over discursive power on the question of how many died and fell ill because of radioactive fallout that could have been prevented. Because how could nuclear energy become an alternative option for future energetics, if accidents could be so severe, as Brown claimed?

In February 2021, earth hosted 443 operational civil nuclear reactors with a total net electrical capacity of 393 GWe [1]. 50 more were under construction [2]. It was only one reactor, featuring only 1 GWe, which due to its disintegration at Chernobyl in April 1986, introduced earth to its first disaster rated seven on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES).

It was only one tank filled with several dozens of tons of liquid radioactive waste from the Mayak reprocessing facilities, which exploded in September 1957 and which was enough to contaminate vast stretches of land in the Urals, forcing 10,180 people to be evacuated and at least 22 villages to be abandoned, while being rated six on the INES [3].

A lesser-known accident happened at the very top of the Kola peninsula in the Russian North, at Andreev Bay, 60km away from the Norwegian border. There, a nuclear waste storage facility suffered a radwaste cooling pond leak, causing contaminated water to flow into the Barents Sea. Clean-up lasted until 1989, and during that seven-year-period hundreds of thousands of tons of radioactive water discharged uncontrolled into the sea with consequences yet unknown. Ultimately, spent nuclear fuel assemblies were sent to Mayak – the very place which suffered the waste tank explosion 25 years earlier.

As of today, there is no definite solution to what we should do with radioactive waste stemming from the industry. Neither do we know, what to do with the nuclear legacy of sites of atom exploitation. The civil and military branches have produced stretches of uninhabitable land, scores of radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel, bombs, events during which radioisotopes were released into air and water, and long-term health consequences for affected people. Thus, earth has suffered significant environmental pollution for the nuclear-driven advancement of human societies in the 20th and 21st century.

Nuclear energy is one of the most potent electricity sources humanity has invented so far. Hence, we witness a nuclear renaissance in Eastern Europe in general and in Russia in particular, during which advocates of nuclear power stress its low-carbon emissions and potential to fill the gap left by coal, gas and oil. States like Sweden and Germany face a similar choice – Shall they place their ambitions for a sustainable future in promoting wind, solar, hydrogen and other renewable electricity sources or in the nuclear industry, with its temptingly vast potential?

A key component for evaluating any answers to this question is the topic of nuclear safety. How sure can we be that problems of the sort mentioned above will not happen again? Nuclear disasters such as at Chernobyl, Fukushima or Mayak are not common and surely do not reflect the whole state of nuclear safety in the global nuclear industry. Nevertheless, they show what can happen if things get out of hand.

The expansion of nuclear energy is closely linked to the development of a technocratic culture, which procures legitimacy through the achievement of economic and political goals. Since nuclear stations are major long-term investments, such a project can only be conducted if backed by either a state, like in China or Russia, or by very rich and stable private companies, like in the USA. In some cases, such as in Japan or France, both spheres link.

If both spheres merge, then it is clear for the industry to have fiscal guarantees and greater influence upon the public opinion on the expansion of nuclear energy. For politicians this is tempting, because the nuclear industry provides a lot of stable jobs, an aura of progressiveness, certain dual-use possibilities and – most important – the promise of the solution for multiple economic problems, such as import substitution for fossil fuels, economic growth through the stable provision of electricity, and political prestige through nuclear high-technology. In short, both help and legitimise each other.

Historically, in such situations a technocratic culture emerges. This culture intrinsically legitimises the sacrifice of important safety principles for the sake of the advancement of the project and economic feasibility. If both spheres merge, who can critically control nuclear safety? When the French author Simmonot, writing about the entanglements between the French nuclear industry and the government, declared that ‘nucleocrats do not sleep’, he knew that the interest for quick profits presented a grave danger for nuclear safety and thus for whole societies confronted with nuclear power plants [4].

Now, when scholars speak of a nuclear renaissance, the Soviet successor state Russia is at the helm of renewed efforts in modernising, promoting and expanding formerly Soviet nuclear energetics. New ex-Soviet reactors are being built in Russia, Finland, Belarus, Turkey, Bangladesh, China and India. Furthermore, some are planned in Hungary and Egypt. How many of these countries link government and nuclear industry and how can we be sure that nuclear safety is warranted by the significance it needs? [5]

So, if proponents of nuclear energy argue for a nuclear renaissance to combat climate change, they should address the question of safety and the links to politics and other controlling institutions in a transparent way. The focus should be on how the safety of nuclear power can be guaranteed and further nuclear catastrophes prevented. Furthermore, we need first to find a solution for long-term radiating nuclear waste. Another unsolved issue is the healing of contaminated landscapes created by nuclear accidents.

Concluding, to legitimise the merging of a nuclear industry and a government is a way to contribute to a technocratic working culture. Such a culture has been detrimental in the past to nuclear safety. The examples of Chernobyl and Fukushima show this clearly. In the current state of climate crisis, we should focus on the rapid development of alternative renewable energetics. To push nuclear energy now might help to curb greenhouse gas emissions – but it would increase the risk for potential radioactive contamination. Therefore, this topic should not be engaged in a technocratic, but instead in a democratic way.

References

[1] See IAEA/ PRIS: Operational & Long-Term Shutdown Reactors, 09 February 2021, https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/WorldStatistics/OperationalReactorsByCountry.aspx [2021-02-10].

[2] See IAEA/ PRIS: Under Construction Reactors, 10 February 2021, https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/WorldStatistics/UnderConstructionReactorsByCountry.aspx [2021-02-10].

[3] See IAEA Press Release: USSR Provides Details of Accident in 1957 at Military Nuclear Plant in Southern Urals, Vienna 26 July 1989, p. 2, and the following report by Nikipelov, B.V./ Romanov, G.N./ Buldakov, L.A. et al.

[4] Simonnot, Philippe: Les nucléocrates (capitalisme et survie), Grenoble 1978.

[5] See International Nuclear Safety Advisory Group: Safety Culture (INSAG-4), Vienna 1991, p. 1.

On 15 June 2023 Eric Paglia, the host of the Polar Geopolitics Podcast and researcher in the division of history of science, technology, and environment at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, interviewed me about the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in Ukraine, its meaning for the war in Ukraine and the geopolitical position of Russia.

You can find the episode here.

Abstract

The recently destroyed Kakhovka Dam and the nearby Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Station are inextricably linked legacies of Soviet energy infrastructure that have become major concerns in the midst of the war in Ukraine. Achim Klüppelberg from the Nuclear Waters project at KTH Royal Institute of Technology is an expert on nuclear energy in Ukraine and Russia, and he joins the podcast to provide an in-depth analysis of the dire situation in the lower-Dnieper region. He also explains the enduring risks and complexities surrounding nuclear energy and infrastructure in the post-Soviet space, including Chernobyl, and discusses an array of nuclear issues related to the Russian Arctic.

Our project at KTH has released a new newsletter, full with stories about what we did during the last months, pictures, and of course publication lists.

If you are interested in the project, make sure to check out our website.

…and ends an era which once was characterised by the promise of abundant cheap energy that was shattered during the disaster at Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986 and buried after Fukushima-Daiichi in 2011. Nuclear energy in this Central European country has always been a contested issue, and the scale of it made it inevitable for society to debate its use.

After World War Two, both Germanies embarked on the nuclear journey to take part in this then futuristic new technology. After the nuclear bombs had been thrown on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it became clear that in order to secure any form of independent statehood a country needed to have nuclear weapon capacities of some sort to protect itself. For Western Germany, this was done through a deal with the USA that technically is still valid today: The US would station some nuclear weapons on Western German soil and in the case of a war against the USSR, West German air planes and fighter pilots would use these bombs as part of a bigger scheme NATO under the leadership of the US had prepared. Eastern Germany also embarked on the nuclear journey, building basically two relevant facilities: a research reactor facility at Rheinsberg and a massive industrial nuclear power plant at Greifswald. After NATO was formed and Western Germany had joined it, the East answered with the creation of the Warsaw Pact, which equally foresaw nuclear protection for the GDR. That being written, it was clear for every German, no matter whether born in Leipzig or in Düsseldorf, that nuclear war in Europe would inevitably lead to the complete destruction of Germany as a whole. Nuclear weapons are after all political weapons: as soon as they are used they lose their purpose and destroy everything. Yet the path a country has to take in order to obtain these weapons is riddled with potentially dangerous stepping stones.

In post-unification years, the nuclear industry tried very hard to always separate the civil usages of nuclear energy from its military roots and implications. While the aftermath of World War II prevented Germany to officially get her own nuclear weapons, at least the Federal Republic did procure every step of the nuclear lifespan on its own territory – with the exception of considerable uranium mining – to have the foundation to create nuclear weapons if at some stage the need shall occur. And that leads us to a very important point often overlooked in the German debate on quitting nuclear energy: the facilities in Gronau and Lingen.

The uranium enrichment facility in Gronau, partially owned by the states of Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany, will continue to produce enriched nuclear fuel (3-6%). Its capacity at the moment is 3,700t of product per year. Its work will not be hindered by the official stop to use nuclear energy. Instead, the enriched uranium will be continued to be exported.

The other facility in Lingen, located in Lower Saxonia, creates fuel elements. Owner of this facility is the Advanced Nuclear Fuels GmbH, which belongs to the French nuclear giant Framatome. Lingen produces conventional fuel elements, nuclear fuel in powder or pellet from, and zirconium alloys. Most produce is being exported. Two of the biggest customers are the disputed Belgian nuclear power plants in Doel and Tihange.

So, the so-called “Atomausstieg” is actually only a partial ending of the active nuclear legacy in Germany. Now a new chapter can begin: that of decommissioning and what Tatiana Kasperski and Anna Storm have coined as eternal care. The country lacks an option for storing nuclear waste and as of now has no concept of how to deal with the scores of irradiated material. Let’s see, how this will be solved. After all, the current situation does also open the possibility to create new ways and understandings of how to deal with the residue of the nuclear age.

Today, 15 April 2023, is a day to celebrate. Generations of people have protested against nuclear energy in Germany. Today a very important step towards a nuclear free country has been taken. Let’s make it a memorable day!

Further readings:

Bauchmüller, Michael: Kernkraft made in Germany, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 11 March 2021.

11 March 2011 (in brief “3/11”) turned out to be a crucial date for Japan and the Pacific Region. On this Thursday afternoon, at 2.46 pm local time, Japan’s east coast fell victim to the Tōhoku earthquake. The earth shook for several minutes, with its epicentre laying about 370 km from Tokyo in the Pacific Ocean. The earthquake caused a huge Tsunami, resulting in a double catastrophe for the Japanese.

As a consequence of both, earthquake and tsunami, several nuclear power plants suffered significant damage. A plant most affected was Fukushima-Daiichi. While the station was more or less able to withstand the earthquake, the following tsunami heavily damaged the electricity grid and destroyed the necessary grid connection to provide electric energy in sufficient amounts to the plant’s cooling system. As anticipated, emergency diesel generators jumped in – but their fuel ran out quickly. In the course of the following days, three of six nuclear reactors suffered meltdowns. In reactor four, serious damage through hydrogen explosions occurred. The catastrophe had begun.

So what happened? In essence, safety considerations were not taking exceptional disasters of the scope of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami into account. In other words, the magnitude of the earthquake and the height of the tsunami were simply greater than the maximum anticipated strain on the nuclear power plant. The plant operator, TEPCO, did not consider an earthquake of magnitude 9 to be a “credible event” in the Japan Trench, as the IAEA concluded in its 2015 report on the accident. The company did not find it economically justifiable to invest in measures to protect the plant against such an event. Per Högselius, professor for history of technology at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, explains that the company did consult historical earthquake and tsunami reports, but the conclusion was that although immense tsunamis did occur from time to time along the Japanese coast, no tsunami higher than 5.7 meters had ever been recorded in the particular stretch of coast where the Fukushima nuclear station was located.

Soon, a Japanese parliamentary panel declared that the disaster was not only a natural one. It was also a human-made one, because official institutions believed that measures taken were sufficient and that the cost-safety calculations were appropriate. This is correct, since humans created this envirotechnical system, in which the nuclear power plant was integrated into the waters of the Pacific Ocean. As Charles Perrow has taught us in Normal Accidents, every technological system that incorporates complicated and potentially risky machines with the operation of human actors, will inevitably lead to incidents and accidents as time progresses. Time was the crucial variable, both in TEPCO’s risk assessment and in reality.

In July 2022 the district court in Tokyo closed a lawsuit against four former heads of TEPCO, investigating their potential negligence in said safety assessments. The court found them guilty and charged them with privately having to pay 13 trillion yen in retribution, about $95 billion at that time. In the opinion of the court, these officials could have prevented the catastrophe if they would have acted appropriately with safety and not profits in mind.

For TEPCO water was both a saviour that made it possible to re-establish the cooling of the molten reactor cores and a medium of contamination at the same time. Currently, the operator struggles with securing the remains of the destroyed reactor cores and storing them somehow safely on land to facilitate decommissioning efforts. Unfortunately, high levels of radioactivity prevent a lot that needs to be done. The reactor cores need permanent cooling to prevent further uncontrolled nuclear reactions. Due to the initial destruction of the cooling circuits and the following makeshift replacements, water was not kept within and reused as coolant, as it leaked into the reactor building. From there, it was pumped out, treated and stored outside the plant. On several occasions, it was ultimately dumped into the Pacific. At the time of writing, no end to this problem is in sight and TEPCO has announced to soon release a significant amount of contaminated water into the ocean.

In the meantime, decontamination work has been conducted in many places in Fukushima prefecture. A huge amount of top soil, saturated with toxic radioisotopes, was dug up and stored in plastic bags on dumping sites. These sites are usually out in the open and expose these bags to the elements, contributing to their deterioration.

Tomoko Otake from the Japan Times writes that “[s]ince 2015, the Interim Storage Facility, which straddles the towns of Okuma and Futaba and overlooks the crippled plant, has safely processed massive amounts of radioactive soil — enough to fill 11 Tokyo Domes — in an area nearly five times the size of New York’s Central Park.” This site unpacks the black plastic bags, filters the soil, and buries it in prepared 15-metre-deep pits. Afterwards, the pit is filled with uncontaminated earth and sealed with a patch of grass. “Areas where the work has been completed look like soccer fields”, writes Otake.

While with this method the contaminated soil is out of sight, it is unsure where the buried radioisotopes will end up. These prepared pits have a drainage system aimed at preventing toxins to enter the groundwater acquifers. That being written, it is unclear how underground migration will eventually turn out. Local residents seem to be in opposition to this practice.

On both spheres, on land and in water, Japanese authorities and TEPCO struggle to get a grip with the ongoing contamination stemming from the destroyed nuclear power plant. Even worse – and here a strong parallel to the Chernobyl exclusion zone can be seen – once contained radioisotopes do not stay at a given location. They recycle through food chains and the environment until they have decayed. Wind, fire, water, erosion, and the life cycle of living beings transport radioisotopes to unforeseen places and accumulate in changing hotspots that in turn might become dangerous to humans. The contamination of ground water, ocean water and soil inevitably leads to a contamination of foodstuff and drinking water. This in turn leads to radioisotopes being incorporated into human bodies, where they make the host sick in multiple and varying ways.

Unfortunately, the meltdowns have taken place twelve years ago and nothing can change that. It is now paramount to find a way to safely decommission the destroyed reactors and by doing so to stop the continuous spread of further contamination, for example through the release of radioactive water into the sea. I hope that that world will continue to support Japan in a joint effort to prevent the worst effects of the catastrophe and to at least find a way to stop the continuous practice of producing more and more contaminated scores of water. This is a problem that concerns everyone and TEPCO is clearly not able to solve it on its own.

As we commemorate today’s 12th anniversary, we should remember that tremendous resources will be needed to contain this problem. It also manifests a stern warning sign that these sorts of accidents – whether it was Chernobyl in 1986 or Fukushima on 3/11 – might repeat themselves at one of the about 500 civil nuclear power plants around the world. Living on an earth that desperately has to tackle climate change, proponents of nuclear energy readily point to this power source as a potential tool to help transform our energy systems into greenhouse-gas-neutral assemblages. I doubt this narrative, as there is no final storage or any anticipated solution for radioactive waste, no comprehensive way to deal with disasters, and no understanding of what it means to care for toxic materials for centuries and millennia to come. If anything good could come out of 3/11, then maybe it can help us to reflect what we are doing to the planet and to ourselves.

Further reading:

Bothe, Julian a. Friedrich, Lisa Marie: Weder Kohle noch Atom, in .ausgestrahlt, 28 February 2023.

Polleri, Maxime: Our contaminated future, in Aeon, 15 December 2022.

SVT.se: Tolv år efter olyckan – kärnkraften åter på frammarsch i Japan, 10 March 2023.

Every writer knows that there are different phases in our work. Of course, the most important phase is the writing phase. After all, it is our job to produce high-quality texts, is it not? Subsequently, every writer also knows that in order to be able to do so, one needs high-quality sources. While working as an historian, having access to valuable source material is paramount in order to write something relevant for the respective academic field. At the same time, the Covid-19 pandemic has made normal schedules obsolete, and many archival trips had to be cancelled or postponed – in my case, since summer 2020. Therefore, I was very grateful to finally be able to go on a crucial archival trip this November.[1] My destination was the vibrant Ukrainian capital of Kiev, and I had three archives stacked with Soviet-era nuclear documents on my to-do-list. Here, I would like to tell you about my experiences and impressions.

Naturally, Kiev is a city with a rich history, reflected in different architectural styles, urban planning and monuments. Kiev has a troubled and at the same time glorious history. Being the medieval cradle of Eastern Slavic principalities, states and nations, having formed the mighty Kievan Rus Empire, which through its Baptism led to the Slavic traditions of Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the cultural, political, and industrial capital of Ukrainians, posing as a major battlefield in World War Two, centring Ukraine’s independence after the collapse of the USSR and recently hosting the Maidan protests, this place emanates historic significance at its different sites. Kiev is also a torn city, in which the current economic crisis, the hybrid-war with Russia, antisemitism and nationalism struggle with opposing ideas on the streets. If we live in a time during which Ukrainian history is written in short intervals, then Kiev is the place to be.

My work led me to three archives. The first on the list was the Central State Archive of Supreme Bodies of Power and Government of Ukraine (Центральний державний архів вищих органів влади та управління України, ЦДАВО). Located in South Central Kiev, the archive is based in a complex of several governmental institutions. The reading room offered a rich ensemble of documents from Soviet-Ukrainian ministries and planning institutions, which proved to be invaluable for the immediate progress of my dissertation.

My second station was the Central State Archive of Public Organisations of Ukraine (Центральний державний архів громадських об’єднань України, ЦДАГО України), where I looked into files from the Communist Party. The archive was located next to the Kiev Region State Administration, along which the massive Lesi Ukrainky Boulevard allowed dozens of cars to speed on ten lanes towards the city centre. Here, I was less fortunate. The CP Ukraine files I ordered offered insights into internal party affairs, but not into any planning aspects of Soviet Ukraine’s energy system.

My third and last station on this trip was the State Archive of Kiev Province (Державний архів Київської області, ДАКО). Inspired by Louis Fagon’s approach of visiting local and regional archives in order to circumvent the occasional quietness in central documents on nuclear issues, I examined local party protocols of the towns of Pripyat and Chernobyl to find out more about water amelioration processes and different important stages of the construction of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Here, lots of exciting issues came to light and I am looking forward to incorporate them into my next article.

Apart from those visits to the archives, I was also able to see the exhibitions at the Holodomor and the Chernobyl museums. Both were very impressive. The Holodomor Museum was located in the Park of Eternal Glory overlooking the Dnepr, in which apart from the museum many memorials for Ukrainian nationalists were placed. There, visitors would see an exhibition showing the horrors of the forced famine in Stalin’s Soviet Union from 1932-33. This was based on many personal testimonials and artefacts from survivors of these times. Their main message was that it was a planned famine created by Moscow as a way to subdue ethnic Ukrainians.

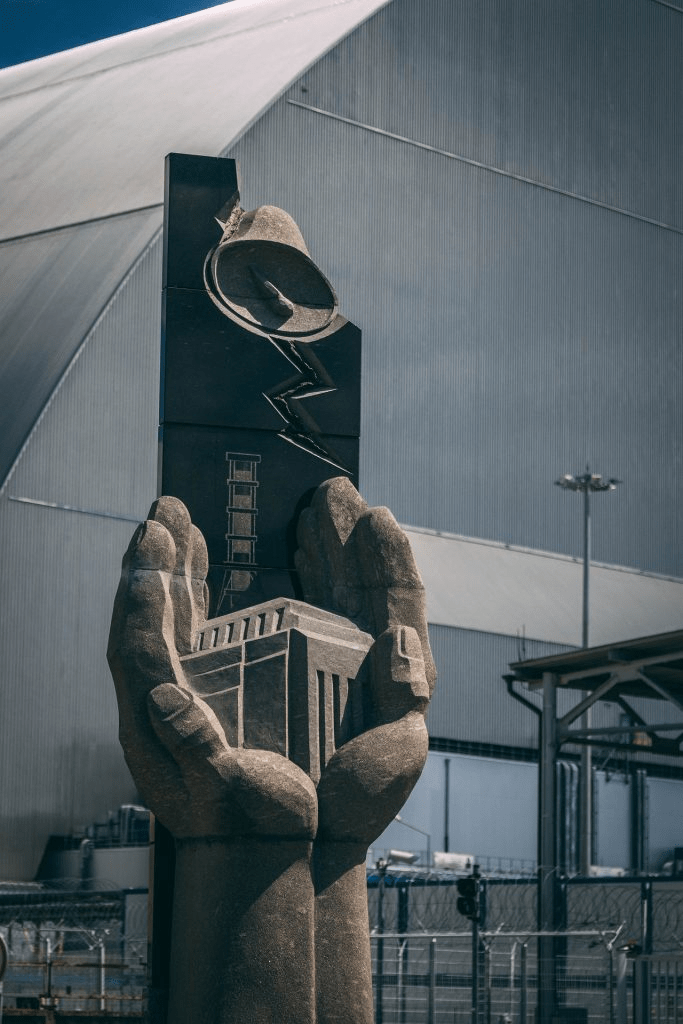

I was very surprised, in a positive way, by the Chernobyl Museum. There, they had collected multiple artefacts of the main protagonists of the catastrophe, such as identity cards and passports from Deputy Chief Engineer Anatoly Dyatlov, or accident-shift-leader Aleksandr Akimov. Selected archival documents along newspaper articles were also on display. Next to them, one could see the flags of the firefighter brigades, uniforms, respirators, and dosimeters. Two whole sections were dedicated to the construction of the first and the second sarcophagus. Following were some dedications to the international solidarity in regard to the mitigation of the consequences of the accident as well as the ongoing help for chronically sick people, such as the “Children of Chernobyl” network. Another room was dedicated to the effects of radionuclides dispersed by the accident to the environment and human society. Here the focus was not to tell a uniquely Ukrainian story, but instead to document the disaster from an international point of view.

Summarising, I am very grateful for this opportunity that arose at this crucial state in my dissertation. Kiev is an exciting place, where so many things have happened and are happening right now. It is definitely worth a trip.

This text was originally published on nuclearwaters.eu on 7 December 2021.

[1] 03 -20 November 2021.